For Derrida, death is a border that itself has no borders, resembling God, and is thus an aporia. In Aporias, published in 1993, Derrida thinks death according to this problematizing of limits, lines, borders, and boundaries.

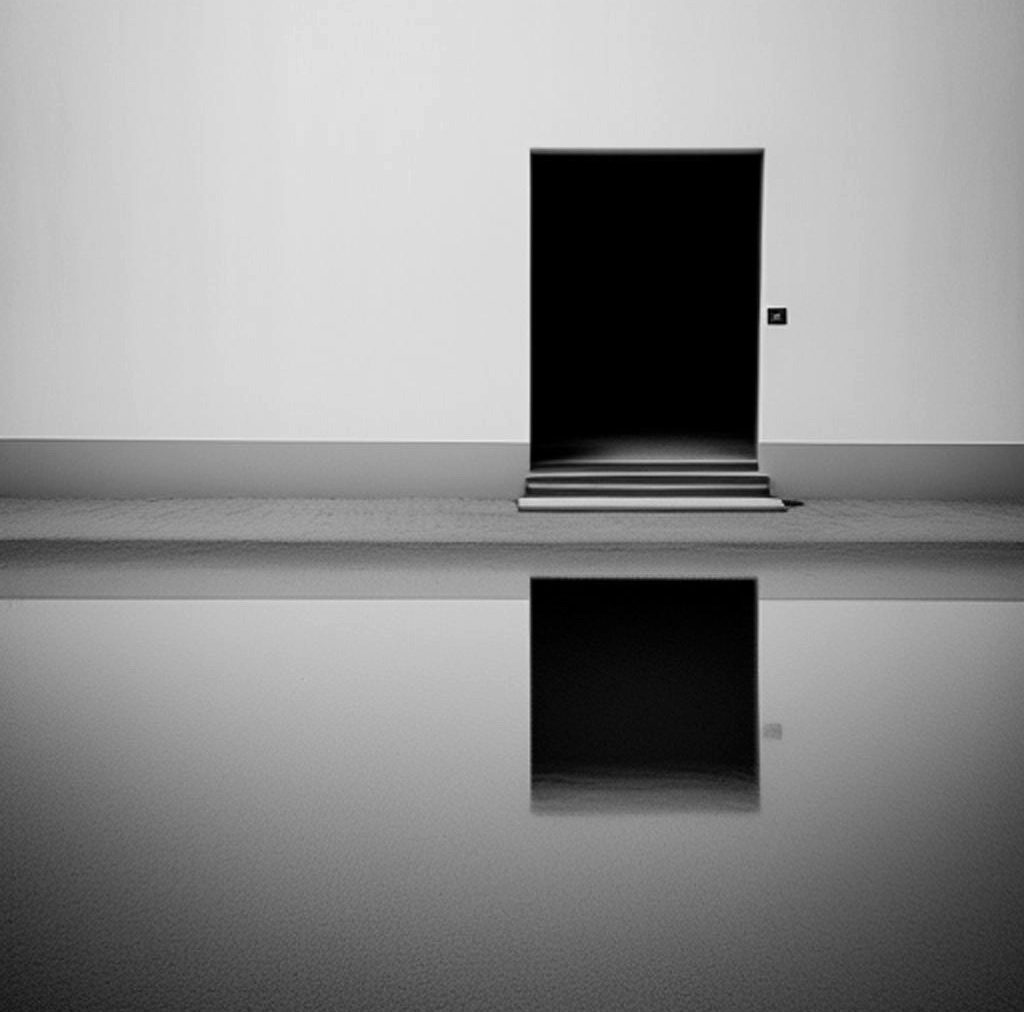

According to Derrida, in most traditions, religions, contexts, and cultures, death is often perceived as a border, a boundary, or an ultimate limit; that is, as a journey over the horizon toward and into the beyond, as a certain passing through an ultimate boundary.

Yet death remains without borders, boundaries, limits, or thresholds, according to Derrida. Death is without borders and boundaries not only because it traverses, renders porous, and passes over all limits, thresholds, and separations, but also because it, as a word, resembles the word “God” in the sense that it cannot hold within itself either a stable notion or a fixed concept.

For Derrida, death resembles God because it neither renders available an undoubtable experience nor refers to a definite, decidable, and decided thing. In other words, the meaning, significance, and that to which death refers cannot be decided, identified, fixed, or rendered stable. Death overflows and exceeds all attempts at rendering limited, fixed, or stable.

This is why, for Derrida, death overflows, disrupts, and exceeds all the boundaries, separations, and limits that would be required in the first place to render possible all crossings, passages, and traverses; that is, all passages of boundaries, all passages through limits, and all passages across thresholds.

This is also why Derrida links together his thinking of death to the term “aporia”, which is an old Greek term conveying and describing an untraversable state or locale that cannot be resolved or thought through reasonable analysis, rational arguing, or dialectical thinking-philosophizing.

Aporias cannot also be contained within any rational discourse as objects of knowledge or objectives of investigations. Hence, for Derrida, aporias are unthinkable to the extent that they offer themselves to thinking.

To think an aporia is to attempt to think the unthinkable; to situate it is to endeavor to name what, by definition, cannot be decided; to identify it is to attempt to recognize what, by definition, is forever evading, according to Derrida.

Aporias, Derrida says, cannot be projected or solved, for they cannot be reduced to mere problems. Aporias are undecided and undecidable states or situations that disrupt, exceed, problematize, and suspend all decided norms, established conventions, and pre-determined duties, moralities, and expectations, opening up new possibilities of deciding, giving, forgiving, inventing, taking responsibility, and being hospitable.

The aporia – as what is untraversable, unknown and unknowable, and undecided and undecidable – pervades death and its limits and affects and disrupts it without limits.

The aporia absolutely disrupts and radically renders unstable all the disciplines that study and investigate death; that is, psychology, history, theology, biology, anthropology, etc. The aporia also affects without limits Heidegger’s existential analysis of death, which, according to Heidegger, must precede any metaphysical thinking-philosophizing of death.

In a word, there is between death, God, and aporias a certain relatedness, destabilized and destabilizing, rendering forever unstable all limits and every limiting, and showing how death is forever disrupting and disrupted by rendering apparent how death, as a limitless limit, is itself impinged upon without limits.

For more articles on Derrida‘s philosophy, visit this webpage.