Sartre’s atheism is radical; it is philosophical and personal, ontological and subjective, phenomenological and poetic; it is the origin, scope, and destination of Sartre’s whole existential and ethical thinking-philosophizing.

Philosophy and Sartre‘s Atheism

In the existentialism of Sartre, Godlessness holds sway; God has no dwelling place; there is no site reserved for God; God is constantly and radically refused and denied.

There is in Sartre’s existential thinking-philosophizing a deep and radical refusal of the view or the suggestion that there might be existing what exceeds and is beyond this world. For Sartre, this world, our world, is human; it is the result of the coming together of consciousness and being.

Even being in-itself, which, according to Sartre, exceeds, surpasses, and is extended beyond the knowing, understanding, and glimpsing of our consciousness, is itself offered to us through this world, through this human world.

Being in-itself is not Plato’s perfect and complete world of Forms, which is beyond our imperfect and incomplete world. For Sartre, there is no world existing beyond this world; there is no ultimate reality existing beyond this reality; reality is human, and it is the only reality that is. The world is human, and it is the only world that is.

The human being, the being for-itself, Sartre says, resides in Being, which is neither divine nor holy. There are no transcendent spheres or regions of Being. Being exceeds and evades holiness and divinity; and there is nothing that exceeds Being, neither worlds nor beings or a divine Being.

In Existentialism Is a Humanism, Sartre says that there is only one universe, a human universe, existing only for us and offering itself to us as an extent. There is thus nothing, Sartre says, that can exist beyond or outside this universe, our universe. This universe in its entirety exists only for us; it is turned toward us, for there is nothing beyond it.

Because the for-itself is an intentional consciousness, it forms a world for itself, it forms its own world. This means that whatever exists outside of this formed world, or whatever lies beyond this world, does not exist for the for-itself. This is why God is impossible.

This is also what Sartre means by “existence precedes essence”. That is, because there is no God, because God cannot exist in this formed world, there is no essence, pre-determined nature, or fixed core residing in us, preceding or exceeding our existence in the world, and deciding or defining us.

Because there is no God, and because there is nothing preceding, shaping, exceeding, and deciding our own unique ways of being in the world, we are abandoned, according to Sartre.

This abandonment is neither a negative leaving behind nor a hopeless forgetting about, but rather our radical freedom and true liberation. This abandonment should not thus be viewed or thought negatively; it should be optimistically welcomed and celebrated in its freeing and liberating.

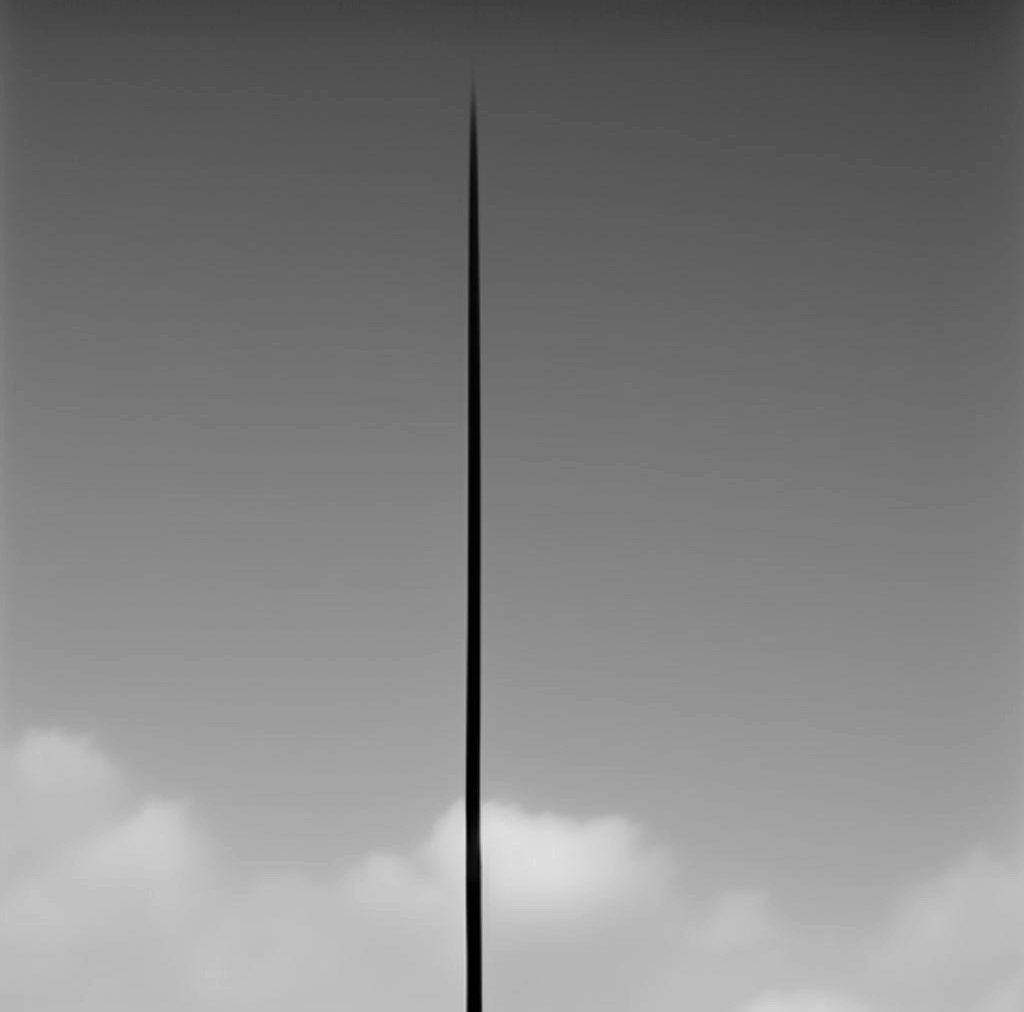

In The Devil and the Good Lord, Goetz, the leading character, links together the absence, impossibility, and non-existence of God with radical and infinite emptiness to render clear how the non-existence of God is itself our radical freedom and true liberation, and to show how the absence of God opens up an infinite space in which we can create and re-make ourselves, our destines, and our lives.

Each minute I wondered what I could be in the eyes of God. Now I know the answer: nothing. God does not see me, God does not hear me, God does not know me. You see this emptiness over our heads? That is God…He does not exist…I have delivered us. No more Heaven, no more Hell; nothing but Earth.

Jean-Paul Sartre, The Devil and the Good Lord

The non-existence of God renders us radically free; it liberates us; it condemns us to freedom. In Existentialism Is a Humanism, Sartre says that Godlessness means that we are completely responsible for our own projects, lives, and destinies.

God died and all transcendence disappeared because of this death; this death has rendered our possibilities infinite. According to Sartre in Notebooks for an Ethics, “in this way, man finds himself the heir of the mission of the dead God: to draw Being from its perpetual collapse into the absolute indistinctness of night. An infinite mission”.

The death of God has rendered life meaningless, valueless, and purposeless. For Sartre, this means that we are now required to create, render possible, and bring about different human and earthly meanings, values, and purposes.

But how are these earthly meanings, values, and purposes to be rendered possible and brought about? According to Sartre, such earthly values, meanings, and purposes need and await the for-itself; they occur only through and because of the for-itself; they occur and announce themselves only when the for-itself fully acknowledges its own radical freedom and absolute responsibility.

This acknowledgment allows the for-itself to able to bring about and render possible different meanings, earthly purposes, and new values; it allows the for-itself to finally realize that selves, projects, lives, and destinies could be repeatedly and continuously formed and re-formed, made and re-made.

What renders these processes of forming and re-forming, of making and re-making, continuous and never-ending, Sartre says, is the freedom residing in the being of the for-itself, the freedom appearing and announcing itself in the site opened up and rendered empty by the death of God.

The Personal-Poetic Aspect of Sartre‘s Faithlessness

To Sartre’s atheism belongs also a personal aspect, or a poetic hope, announcing itself simply as radical faithlessness. Perhaps this absolute lack of faith is what grounds Sartre’s philosophical and ontological views and arguments, in which there is no site reserved for God.

In Words, Sartre says that he discovered the non-existence of God when he was 12: “God at once stumbled down into the blue sky and vanished without explanation: He does not exist, I said to myself …and I thought the matter settled.”

Also, in his Entretiens with Simone de Beauvoir in 1974, Sartre revealed that despite having deep and complex arguments for his radical atheism or absolute faithlessness, his radical non-belief in God was not philosophical, but rather deeply personal.