On The Vanity and Suffering of Life is an essay that appears in the second volume of Schopenhauer’s The World as Will and Representation. As the title of the essay indicates, that about which Schopenhauer speaks in this essay is not only our suffering in life, but also the futility, uselessness, and pointlessness of our lives, in which there is nothing but suffering, frustrations, and pain.

The Will, Suffering, and Vanity

For Schopenhauer, life is constantly filled with suffering, pain, and frustrations; it is also pointless and futile. The origin of our suffering in the world and the pointlessness of our existence, Schopenhauer says in the essay, is the will. The will is the origin of all suffering and pointlessness. Suffering and vanity take place and hold sway because of our blind following of the blind will.

The will, Schopenhauer says, loves life and sees it as a marvelous opportunity, yet life, to a large extent, is nothing but the domain in which the will’s infinite yearnings are frustrated, disrupted, and rendered impossible.

By seeing life as nothing but that in which the frustrating of the will takes place and constantly confirms itself, and hence by placing pointlessness and suffering into the heart of existence, Schopenhauer renders pain positive and essential and happiness negative and accidental.

This means that suffering, for Schopenhauer, is neither brief nor rare, but rather constant and dominant. In other words, suffering is not the brief negation of happiness or the fleeting absence of pleasure. It is happiness itself that is brief, rare, and fleeting. Happiness is the brief negation of suffering, pain, and frustration.

Schopenhauer thus reverses the view that there is happiness through which fleeting and rare instances of suffering and pain are scattered into that there is nothing but suffering and pointlessness in which brief and scattered moments of happiness announce themselves and are experienced.

Life, for the most part, is thus neither marvelous nor good, and it cannot be viewed or thought of as a worthy happening, endeavor, opportunity, or experience. Life is something that must be denied and turned away from rather than affirmed or welcomed; it is pointless and painful. (This article explains Schopenhauer’s view that ”all life is suffering”)

The Nature of Things and Suffering

“Everything in life proclaims that earthly happiness is destined to be frustrated, or recognized as an illusion. The grounds of this lie deep in the nature of things. Accordingly, the lives of most people prove troubled and short. The comparatively happy are often only apparently so, or else, like those of long life, they are rare exceptions; the possibility of these still had to be left, as decoy-birds. Life presents itself as a continual deception, in small matters as well as in great.”

Arthur Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Representation

Suffering and unhappiness are rooted in “the nature of things” itself; they are neither accidental nor temporary. By placing suffering, pain, and unhappiness into “the nature of things”, that is, into the heart of life and existence themselves, Schopenhauer confirms his view that because of the will’s constant and infinite cravings and strivings, there is nothing but constant frustrations, failures, and disappointments. That is, because of the will’s infinite cravings, suffering and pain will always hold sway.

Schopenhauer places the human being and life in a relation in which life always tricks and plays with the human being: “Life presents itself as a continued deception . . . If it has promised, it does not keep its word, unless to show us how little desirable the desired object was”. Happiness is never present; it is never in the present, it is always either in the past or in the future. The present is constantly hollowed out and lacking because of its incessant turning toward an illusory and distant future or a blurred happiness in the past.

Life is always torn between a blurred past, which perhaps never happened, and a distant future, which perhaps will never happen. Life, for Schopenhauer, is thus “a business that does not cover its costs”.

“We feel pain, but not painlessness; care, but not freedom from care; fear, but not safety and security. We feel the desire as we feel hunger and thirst; but as soon as it has been satisfied, it is like the mouthful of food which has been taken, and which ceases to exist for our feelings the moment it is swallowed. We painfully feel the loss of pleasures and enjoyments, as soon as they fail to appear; but when pains cease even after being present for a long time, their absence is not directly felt, but at most they are thought of intentionally by means of reflection. For only pain and want can be felt positively; and therefore they proclaim themselves; well-being, on the contrary, is merely negative.”

Arthur Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Representation

Schopenhauer notices that humans rarely notice or acknowledge the great things that they might have as long as they have them, which are health, youth, and freedom. Such blessings are only noticed when they disappear and are lost. This is always the case because suffering is felt more than happiness, suffering is felt more than the absence of suffering: “We become conscious of time when we are bored, not when we are amused . . . our existence is happiest when we perceive it least; from this it follows that it would be better not to have it”.

Schopenhauer’s statement that “our existence is happiest when we perceive it least; from this it follows that it would be better not to have it” should not be read as a view recommending suicide. Schopenhauer does not only refuse suicide, but also sees any thinking-philosophizing that recommends it as thoughtless and hollowed out. This statement only means that the life that blindly and thoughtlessly follows the demands of the will should be denied and turned away from in favor of and toward a life that thinks against and attempts to deny the will as much as possible. (This article introduces Schopenhauer’s views on suicide)

The Good and Evil in the World

Schopenhauer sees the questioning and inquiring regarding whether there is more good in the world than evil or whether there is more evil than good as pointless and worthless because evil cannot be either banished from the world or counterbalanced in the world.

It appears to be difficult for the human mind, Schopenhauer says, to accept the mere existence of evil. This is why evil has always given rise to philosophical questioning and poetic expressions. Schopenhauer’s whole essay is full of quotes from classical and modern philosophers, writers, and poets showing, expressing, and speaking of the unhappiness, pain, and suffering permeating the world.

Existence is undesirable, Schopenhauer affirms repeatedly. Human existence is full of pain, unhappiness, and suffering, and there is pointlessness and uselessness lying at the heart of this tormented and anguished existence: “We have not to be pleased but rather sorry about the existence of the world; that its non-existence would be preferable to its existence; that it is something which at bottom ought not to be”.

“Man Is a Wolf for Man”

Another factor increasing suffering, multiplying unhappiness, and rendering existence even more futile is how human beings treat each other: “The chief source of the most serious evils affecting man is man himself. Man is a wolf for man”.

The example that Schopenhauer offers in order to support his view that “man is a wolf for man” is the example of world conquerors or what he calls “archfiends”. These “archfiends” set people against each other and tell them: “To suffer and die is your destiny; now shoot one another with musket and cannon and they did do so”. Other examples showing how “man is a wolf for man” are slavery and child labor. Such examples, for Schopenhauer, show the human being’s “boundless egoism…even wickedness”.

Human beings, Schopenhauer says, are heartless toward each other; they are unjust, unfair, and cruel: “In general, the conduct of men toward one another is characterized as a rule by injustice, extreme unfairness, hardness and even cruelty; an opposite conduct appears only by way of exception. The necessity for state and legislation rests on this fact, and not on your shifts and evasions”. (This article explains Schopenhauer’s views on egoism)

The Being of the World

Schopenhauer says that the problem lies in the Being of the world, its origin, and nature. The Being of the world has always been vague, unclear, and concealed from us. Hence, the world has always been a philosophical problem.

Because the Being of the world has always been a problem, the world has always brought about inquiring, astonishment, thinking, questioning, and investigating. The Being of the world is a philosophical problem and there is no philosophical system or structure, no matter how perfect or complete it is, that can completely answer or totally think this problem.

Any attempt at thinking the Being of the world is forever destined to incompletion and exhaustion. There will forever be what is unexplained and unexplainable within any attempt at explaining the Being of the world, there will forever be that which is unsolvable within any attempt at solving the problem of the Being of the world.

Schopenhauer sees the will-to-live as the fundamental truth of the existence of the world and links it together with the Being of the world, for it confirms the mysteriousness and inexplicability of the Being of the world. The will-to-live also, according to Schopenhauer, shows why the world never satisfies us, since “only a blind, not a seeing, will could put itself in the position in which we find ourselves”. What Schopenhauer means here is that we ourselves are blind followers of the blind will to live. A blind leading a blind; a blind following a blind.

Human Existence as a Debt and the World as a Battleground

Human existence, for Schopenhauer, is not a gift and it should not be called or thought of as a gift, but rather as a debt: “Far from bearing the character of a gift, human existence has entirely the character of a contracted debt. The calling in of this debt appears in the shape of the urgent needs, tormenting desires, and endless misery brought about through that existence”.

We spent our whole lives doing nothing but paying off the interest of this debt, a debt that only our death can repay in full: “As a rule, the whole lifetime is used for paying off this debt, yet in this way only the interest is cleared off. Repayment of the capital takes place through death”.

The world, for Schopenhauer, is a “battle-ground”, in which “tormented and agonized beings…continue to exist only be each devouring the other”. The most knowledgeable beings in this battleground feel pain the most. Schopenhauer links together knowledge and intelligence with feeling and says that “the capacity to feel pain increases with knowledge”. Hence, the human being feels pain and suffering the most: “In this world the capacity to feel pain increases with knowledge, and therefore reaches its highest degree in man, a degree that is the higher, the more intelligent the man”.

Against Optimism and the Optimists

At the end of the essay, Schopenhauer attacks and argues against the optimists who see this world as “the best of all possible worlds”:

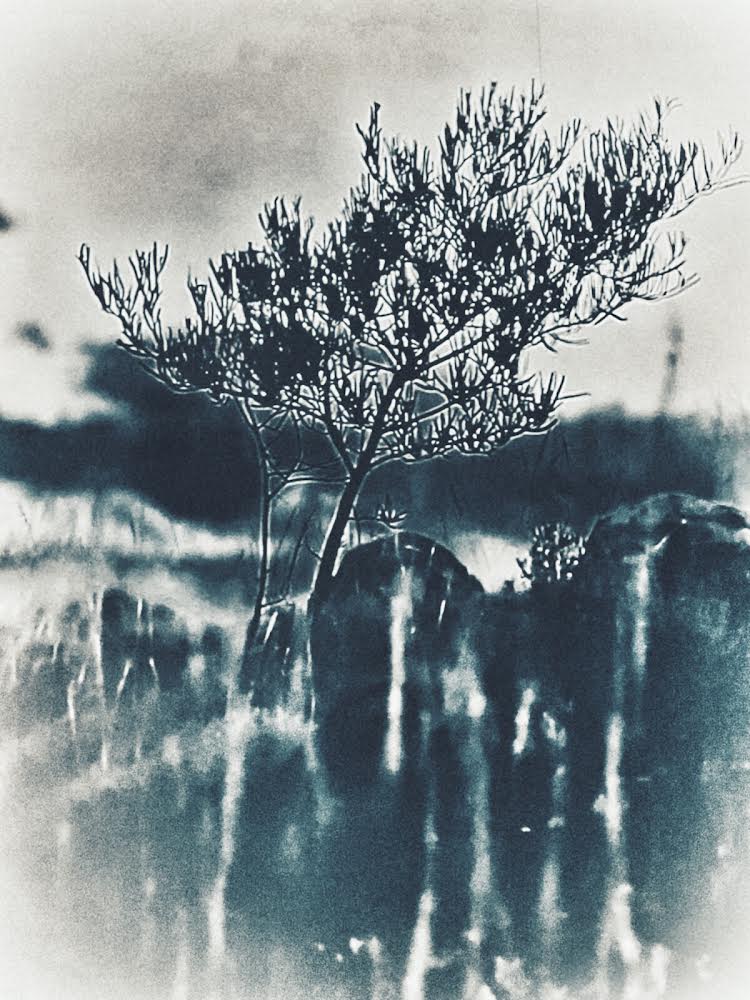

“An optimist tells me to open my eyes and look at the world and see how beautiful it is in the sunshine, with its mountains, valleys, rivers, plants, animals, and so on. But is the world, then, a peep-show? These things are certainly beautiful to behold, but to be them is something quite different.”

Arthur Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Representation

Our world is not “the best of all possible worlds”, but rather the worst of all possible worlds. Our world is the worst possible world because there is nothing worse than it could have ever existed, since in this world, our world, there is nothing but suffering, struggle, and destruction:

“Nine-tenths of mankind live in constant conflict with want, always balancing themselves with difficulty and effort on the brink of destruction. Thus throughout, for the continuance of the whole as well as for that of every individual being, the conditions are sparingly and scantily given, and nothing beyond these. Therefore, the individual life is a ceaseless struggle for existence itself, while at every step it is threatened with destruction”

Arthur Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Representation

Optimism, for Schopenhauer, is illusory, destructive, and false because life is neither desirable nor happy and also because it encourages us to believe and think that pleasures and happiness are our destiny and belong to us, but, since suffering and vanity always take place and constantly hold sway, happiness never occurs and pleasures are rarely experienced.

Because of the optimists and our optimism, we might believe that we have suffered injustice when we undergo that which is painful or undesirable, but, as Schopenhauer insists in the essay, there are no injustices, it is merely the world, it is merely our existence in a world in which there is nothing but frustration and anguish. In other words, what we experience when we undergo what is painful is not an injustice, but rather life itself.

This is why Schopenhauer says that “It is far more correct to regard work, privation, misery, and suffering, crowned by death, as the aim and object of our life . . . since it is these that lead to the denial of the will-to-live”. Schopenhauer ends this essay with some quotes on suffering and pain and says that if he were to write down or record all the great thinkers’ comments on suffering, the list would be infinite. (This article summarizes and explains Schopenhauer’s pessimism)

For more articles introducing Schopenhauer’s philosophy, visit this webpage.